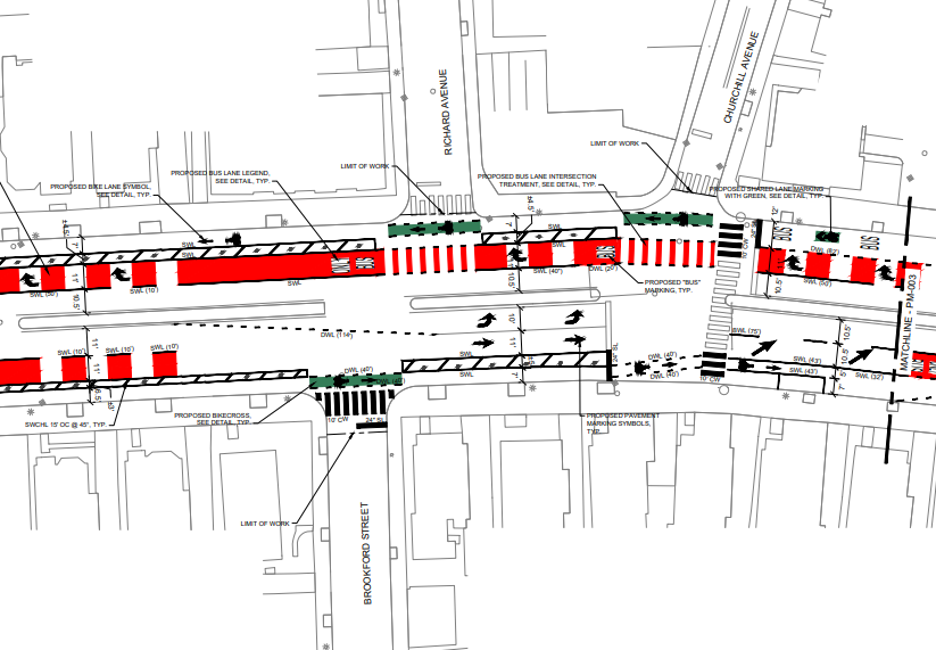

REPORT ON RECENT DESIGN PLANS FOR MASS. AVENUE (and a History from 1775-2022) by Stephen Kaiser3/9/2022 HISTORY OF PLANNING AND CONSTRUCTION FOR MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE: 1775 to 2022 1775 … Great Road became the pathway for militias and British soldiers during the battles of Lexington and Concord. 1840s … Extension of railroads from the Boston Wharfs to harvest ice from Fresh Pond and ship the ice all over the world. The farmers' lobby was so strong that the railroad was forced to build below-grade with a bridge at Porter Square for cattle drives coming down Great Road into marketing pens in North Cambridge. 1850s … A single track connection between the Lowell rail line in Somerville was made to the Fitchburg tracks. Its primary freight advantages gave it the name “the Freight Cutoff.” It crossed Mass Avenue at Cameron Avenue. 1890s … In the Streetcar craze of the 1890s, dual tracks were laid down in the middle of Mass Avenue extending into Arlington and Lexington. 1956 … With the post-WWII decline in streetcar service, the two center tracks were discontinued. Trolleybus operations were substituted instead. 1952 to 1956 … The Rand Estate, a large orchard, nursery and set of country houses fronting on Porter Square were owned by Harry and Mable Rand. They donated it to the City of Cambridge, hoping for its preservation. The property was a 19th century throwback to country times before the streetcar suburb, overlapping with Orchard Street and extending to Elm Street in Somerville. The City sold it to a private developer, who cut all the trees down and built a shopping center. 1958 … Mass Avenue was entirely rebuilt as an urban arterial road with a five-foot concrete median, trolley poles and wires for trolley-bus operation between 1958 to 2022. 1960 to 1967 … North Cambridge resident and Congressman Tip O’Neill performed yeoman service in stopping the Inner Belt expressway through Cambridgeport and East Cambridge. 1985 … Construction completed on the Red Line to Davis Square in Somerville and Alewife. Today it is the route for the Minuteman bikeway and Community Path. (with the Red Line tunnel underneath). 1995 … The shopping center was given a special phase in the lights at Porter Square so patrons did not need to make U-turns on Mass Avenue. Action by Sue Clippinger. 2000 … Lauren Preston resigned as City Traffic Engineer. The position of City Traffic Engineer was abolished by Sue Clippinger. 2000 to 2005 … An initial effort to locate bike lanes on Mass Avenue was attempted by vigorous Bike enthusiasts, but they were defeated by massive resident opposition. 2015 … Primarily through the work of Community Development, a city-wide bicycle plan was developed, later updated in 2020. 2016 … The City Council passed Vision Zero as a new policy with a goal of reducing all transportation injuries to zero, including fatalities. It also sought to increase “safe, healthy, equitable mobility to all.” Its goals were comprehensive, idealistic and applied to all modes of travel. The goal was to create “the collaborative framework” needed to meet this goal. 2017 … A design session was held under the sponsorship of NACTO, the National Association of City Transportation Officials. Planners from across the nation came here with the goal of making Cambridge one of four “Transit Accelerator Cities” in the nation. Mass Avenue was envisioned with bus lanes and other transit services, including pedestrians and bike lanes. From this NACTO design created by 130 planners, North Mass Avenue was eventually transformed from a transit project into a bike safety program. 2017 … Participatory Budgeting had a major role in starting bike lane programs. One of the suggestions was to create a network of bike lanes in the city. Consultant Kleinfelder took over further work and submitted a work proposal to the city, to be done initially under Community Development supervision and later Traffic & Parking. Quick-Build became the preferred non-traditional design method, to be combined with the NACTO Plan. Tasks excluded from the Kleinfelder work : ADA compliance … “Collecting traffic volumes” … “Evaluating transit performance” … “Observing traffic compliance” … “Collecting speed data” … “Conducting crash analysis” … “Evaluating winter maintenance” … “Evaluating retail access with a survey” … “Evaluating retail success. ” All of these omissions became criticisms of the Quick-Build process. 2018 … Contract amendments expanded work to many more Quick-Build projects. 2018 … City Council released a Vision Zero Action Plan. 20-mph speed limits were established for many Cambridge streets. 2019 … The Cycling Safety Ordinance was passed by the City Council, establishing goals of separated bicycle lanes and Quick-Build methods. This policy was strongly supported by a group called Cambridge Bike Safety, which included many activists from A Better Cambridge, a group supporting housing issues, in a creative example of members of one front group moving into another one. The primary focus had a safety focus for bicycle facilities, and not all modes as the Vision Zero required. 2020 … Amendment to Ordinance Section 040 was added to specify deadlines for action. 2021 … Citizens and local businesses protested against losing all parking along North Mass Avenue; political discussions continued on replacement sites, short term parking and loading zones. Businessmen reported severe losses due to loss of parking. 2022 … A City Councilor introduced the concept that small businesses were undesirable along Mass Avenue and that denser development was preferred. Thus the primary lobbying goal appeared to favor new development and not bike safety. 2022 A new design for Intermediate construction between Porter and Harvard Squares was presented by the Public Works Department. Removal of the median was key. Half the parking was restored. THE NEW DPW ALTERNATIVE The primary innovation added on February 16, 2020 was to remove the median in the section between Roseland and Waterhouse Street. Median islands would be retained at crosswalks. A few days later the approved concept was extended to include Beech-to-Dudley. It allowed half the parking to be restored. In addition a new underground corridor five-feet wide will be created for public utilities such as sewers. Some sections of Mass Avenue are wider than others : restoring some parking on both sides may become possible. POSSIBILITIES FOR LEGAL CHALLENGE The ordinance makes no mention of protected bike lanes of any sort, so when the Cambridge Bike Safety group urges protected lanes it is asking the city to take action the City is not authorized to do. Since late last year, critics have raised several questions about the legal status of the Cycling Safety Ordinance. Vision Zero is a policy, and not a binding ordinance. It establishes a goal of improving safety for all modes of transportation, while the focus of the Ordinance is on bicycles only. As a policy and regardless of basic virtues, Vision Zero has limited legal standing. The balance of power between Manager and Council under the Plan E Charter has survived for years on deference to the manager in his freedom to run the city consistent with policies set by the Council. Recent referendum questions have been adopted to require City Council approval of all appointments by the manager, and it appears the sanctity of Plan E may be slipping. The City Council took a gamble by adopting the Bike Safety Ordinance, and if parts of it do not work out, the popularity of a more active Council may be undermined. The recent assertion of a new plan for Mass Avenue suggests a return to design initiative by the Manager, and less interference by the Council. A direct legal appeal to Superior Court on a claim of Plan E violations may still be possible, but must pass through numerous court appeals. However, Plan E has been declining in popularity for a quarter century. The Cambridge Civic Association was a champion of Plan E since the 1940s, but went out of existence around 2005 and is not available to defend the city manager form of government. A more intriguing question is one of constitutionality, of consistency with the State Constitution. In 1779, John Adams penned his draft of the Constitution with its beginning Declaration of Rights, similar to a bill of rights. Over the years many amendments have been made, but Article 7 remains unchanged from its original 1779 formulation : Article 7. “Government is instituted for the common good; for the protection, safety, prosperity and happiness of the people; and not for the profit, honor, or private interest of any one man, family, or class of men …” This understanding refers to cases when the common good and profits diverge, as Adams noted during his years in government service. By this reading, profits could not result from government actions, such as real estate benefits for the fortunate few resulting from the Cycling Safety Ordinance. A sudden loss of parking causing reduced business revenues is contrary to the common good when small businesses are forced into bankruptcy, resulting in “fire sales”of property to interested buyers who are interested in new dense development along Mass Avenue. One City Councillor in discussions with citizens introduced this element that the loss of small businesses could be a benefit if it triggered dense growth for new development. The creation of special interest profits triggered by government actions would not be allowed under Article 7. Article 7 has not been cited frequently in Massachusetts case law, although it has been briefly mentioned in consort with other rights in court arguments, notably Hillary Goodridge vs. Department of Public Health, SJC-08860 440 Mass.309 p. 316 (2003). The ultimate decision would need to be made by the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. The advent of a new compromise plan for Mass Avenue might diminish the relevance of Article 7 at Mass Avenue. Article 7 could still apply where damage to existing businesses has already been done, as with the Quick-Build plan. Even if the new plan were adopted today, the matter could be entered into court by a joint suit of Mass Avenue businesses seeking damages from the City for its actions in approving the Quick-Build project on Mass Avenue between November 2021 to the time that the parking spaces were restored. In the parlance of the court, lobbying groups who argued for the removal of parking could have been identified as “unindicted co-conspirators” coincident with the original action of approving the Quick-Build contract. ===================================================== The new Intermediate construction plan for Mass Avenue with removal of the median and restoration of half the parking can serve as the basic platform to resolve additional problems along Mass Avenue that have existed for sixty years. · U-TURNS ALONG MASS AVENUE In 1958, a median five-feet wide was inserted along Mass Avenue between Cambridge Common and Alewife. At side streets there were breaks in the median to allow turns in and out of those streets. For decades there were difficulties making extremely awkward U-turning movements. The “solution” developed by City officials was to label some median breaks for “No U-Turns” while refusing to post signs where U-turns were to be allowed. The result was that over the years the median area of Mass Avenue became increasingly ugly. This view of Mass Avenue on the approach to Cambridge Common illustrates the resulting clutter in the median, with eight signs banning U-turns. U-turns remain a problem along the entire length of the Avenue. The solution to the U-turn problem comes from a most unlikely source : the Quick-Build treatment of Churchill Avenue. This idea entails adding a turn lane serving left turns into Churchill Avenue and U-turns inbound-to-outbound. This idea is the only noteworthy engineering invention in the Quick-Build design. At Churchill Avenue the bus lane is discontinued and the turn lane is added. Cars and buses are briefly merged into a single lane. U-turns can be made with signal timing holding back outbound traffic (including bicycles) to allow unimpeded turns to reverse direction. The U-Turn move is shown below in GREEN. Arriving U-turn vehicles queue on Red in the turn slot as outbound traffic flows on green. With outbound traffic stopped with a red light, cars in the U-turn lane are given a green light to turn unobstructed. Any traffic coming out of Churchill Avenue can next go on green, while other traffic is stopped.  The sequence ends with Outbound Mass Avenue traffic starting again on green, while the turn slot and Churchill Avenue show red.

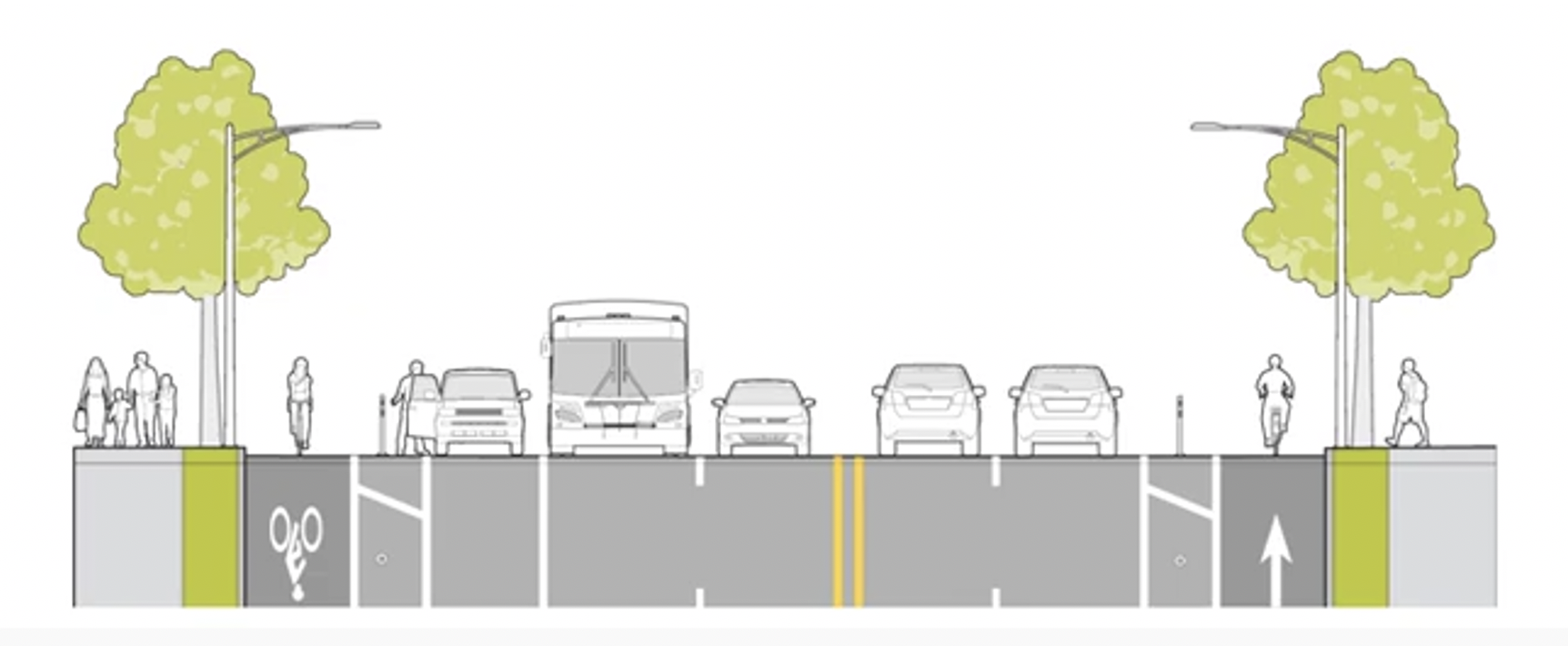

A variation on the Churchill Avenue design is to utilize a short turn lane … a vehicle travel lane … and combine the bus lane with the bicycle lane for a short distance. The problem of dangerous left turns onto or off of Mass Avenue could be controlled by flex posts arranged down the centerline of the road. All left turns can be made by traveling to a turn slot, making a U-turn and either continuing straight or turning right. There is a slight increase in distance traveled, but the safety of the movements is greatly improved. There may be other good ideas on dealing with U-turns and we should discuss them all. · BUS LANES, BIKE LANES and PARKING : HOW DO THEY FIT TOGETHER? For any road sections with parking, there can be four uses for the pavement : regular vehicle travel lane, bus-only lane, bike lanes and parking. There may also be buffer zones associated with the bike lanes. Today, with no parking, the road use from the median is : * Travel Lane … Bus Lane ….Buffer … Bike Lane Two options for the bike lane with parking are : (A) … Travel Lane … Bus Lane … Bike Lane … Buffer … Parking (B) … Travel Lane … Bus Lane … Parking … Buffer … Bike Lane Each version (A) or (B) has special plusses and minuses. (A) is similar to the existing bike lane from Dudley to Harvard. A four-foot buffer would be needed to protect the bike lane from opening car doors. The bus-lane would be right next to the bike lane and would not have a buffer. The bike lane would have no protective barrier offered by a line of parked cars. However, fast bikes could travel in a bus lane and bikes could shift in and out of the bus lane to move out of the way of buses. Parked cars pass over the bike lane arriving and leaving. Illegally parked cars could block the bike lane and/or the bus lane. The same result for loading zones. (B) is like Mass Avenue near Albany Street in Cambridgeport. The bike lane stays close to the curb and has a buffer against right-doors opening on parked cars. The parked cars serve as a physical protective barrier for bike riders. However, any bike riders using the bus lane could not easily bail out and use the bus lane. Left-side car doors when open could be hit by passing buses. Cars are less likely to park illegally in the bus lane. Loading zones might be able to combine the parking lane and the buffer. There are arguments here on both sides, and a healthy discussion among cyclists and businesses should follow a balancing of the pros and cons. Existing bike lane widths along Alewife-to-Dudley vary between four and eight feet. An improved design should reduce this variation and result in bike lanes of more consistent width and fewer zig-zag movements. PARKING POLICIES : LONG TERM PLANS AND MAKING GRADUAL CHANGES The first priority for the city is to ensure that there is a parking mitigation plan for Alewife to Dudley, with a goal of providing 40 replacement spaces (not on residential streets) by March 15. Next is to begin sketching out a Master Plan for the entire Alewife to Harvard corridor, to make sure that the four sections are compatible and consistent to the maximum extent possible. The primary variations will be in the designation or deletion of separate bus lanes, especially at Porter Square. Street widths should be measured more carefully to determine where two-sided parking is or is not possible. Parking policy should be to achieve at least a 50% retention of parking spaces in each section and a temporary off-street parking plan for the remaining 50 percent. Each year the total amount of parking may be reduced by 3 percent following the Copenhagen rule of gradual parking reduction, spread over several decades. There should be no sudden parking removals as happened in 2021 for Alewife-to-Dudley. Zurich, Switzerland should be studied as an example of a large city that sought to reduce parking and improve bicycle facilities, but did not get buy-in from the community. CDD should make a list of the cities that produced successful programs and those that failed. The long-run goals for the City should be spelled out very clearly, as many European cities have done. It appears that Cambridge planners would like to see fewer cars in the city, less parking, more bikes and better transit. City officials should spell these out clearly, and have a step-by-step program to achieve these goals. The Envision Cambridge master plan fails in that endeavor. A long-range plan should extend twenty-five years into the future, with all changes made gradually, except for transit improvements, which can be instantaneous. There should be a gradual phase down of some but not all parking. Special provisions made to retain parking for the elderly and disabled. The removal of parking along Mass Avenue threatens to take away physical protection that pedestrians now have on sidewalks. Parked cars protect pedestrians from errant speeding cars that might spin off the road and enter space reserved for pedestrians. Pedestrians discover that this protected space has now been taken away by a bike safety plan. The double tragedy is that bikes are given no more protection than the newly exposed pedestrians : they too are exposed to errant vehicles. In anticipation of changes in street operations in coming years, we should learn the lessons of Amazon and the rise in package delivery – while shopping malls are collapsing as business enterprises. The success of small businesses along Mass Avenue should be seen as a remarkable achievement. However, deliveries and pickups means more short-term, often illegal parking, with inadequate loading zones. It is the Amazon-Uber-Lyft future we have not adequately planned on. We need thoughtful planning for the future. Certain technologies trumpeted in the past are unlikely to become practical. They include one percent technologies (scooters, motorcycles) and defunct “solutions” (horses & wagons, cable cars, mopeds, Segways, helicopters and automated cars). This last item was the fad of 2016 and has failed to produce a single robot car that can operate in snow or heavy rain. The lesson is to avoid all technologies that have not been fully tested and proven safe for use by the public. The one new technology that looks impressive is early work on revolutionary batteries, so that battery-buses will likely become more practical in all types of weather. TROLLEY BUS and TRANSIT OPTIONS The ending of Trolleybus service in Cambridge should be seen as an historical loss, yet it has happened with streetcars and horse-drawn wagons. The advantages are improved operations for the Fire Department ladder trucks, and the visual removal of trolley poles and wires. It should not be surprising that MBTA policies have produced confusion about the future of trolleybus operations. It appears that on March 12, 2022 trolley bus operations will be stopped and replaced by diesel hybrid buses operating out of Harvard station. The future of the trolley poles and wires is uncertain. The MBTA must deliver a coherent plan for these poles and wires. A reasonable goal is to remove all wires and poles by the end of 2022. Safety problems exist for buses pulling in and out of bus stops and engaging in weaving actions with bikes in bike lanes. More thought needs to be given to how bikes and buses work with the new street arrangement. Provisions for loading zones appear unduly primitive. What happens when buses encounter illegal stoppage or parking in the bus lane ? Having a bus lane for only six buses an hour is a primitive concept compared to New York’s Lincoln Tunnel which has 400 buses an hour. Where is the future for Route 77 bus service? Will it remain one bus every ten minutes, or could we triple the service with three-minute separations between buses? Where are the proposals for better quality service on all bus lines and especially on the Red Line? While planners promise more reliable bus service on the Route 77 line, they show no awareness of existing bus bunching and the potential for future bunching to continue with or without Quick-Build plans. Claims for improved reliability of bus service will be unfulfilled unless we deal specifically with the bunching issue. Observers have reported up to four 77 buses in a bunched group. Rail or bus, the problem occurs in almost all transit operations around the world. MBTA methods to measure and control bunching of 77 buses are nonexistent. A small part of the problem is caused by the design of lane configurations and traffic signal operations. Far too much bunching is caused by uneven spacing of buses at the beginning of the routes, as determined by personnel called starters. The ideal solution is even spacing at the beginning of trips and monitoring of bus spacing during trips so that buses do not bunch up. Proper spacing and reliability of buses is normally seen as the responsibility of the MBTA and cannot be achieved through road design alone. Meanwhile, the MBTA is doing an inadequate job of controlling bunching. City policies for better transit are too dependent upon being obedient to MBTA plans. Cambridge officials in their own best interests should prepare and adopt monitoring methods to assist in keeping buses evenly spaced and unbunched. City officials should use mitigation funds from major developers to prepare operational improvement plans for both bus and Red Line bunching control. We need better ideas for improved transit if hopes are fulfilled for a future Cambridge with fewer cars and less traffic. Cambridge should take the lead and hire competent traffic and transit engineers in Community Development and Traffic & Parking to complete the job the MBTA will not do. ANALYSIS AND CONCLUSIONS Concerns over loss of parking continue with each passing day, and City officials have not implemented a plan for substantial replacement parking along the Alewife-to-Dudley corridor.. The inbound bus lane serves no useful purpose today because there is no severe inbound congestion that justifies the benefits of having a special lane to bypass congestion. Outbound, there is traffic congestion at Porter Square and at Alewife, so an outbound bus lane can allow buses to bypass backed-up traffic. Therefore, the City should remove the inbound bus lane. The 11 feet width of the bus lane can be repainted as a seven-foot parking lane and a four-foot buffer to protect bikes from "dooring." The result is a restoration of 40 spaces of metered parking The work involves no construction and could be completed in a week. In 2000, the position of City Traffic Engineer was abolished. Until this position can be re-established, Cambridge should retain McMahon Associates to perform this function. McMahon should review all changes proposed for Mass Avenue, including changes to rectify Quick-Build work already done. Competent traffic engineering services should be sought to assist the Traffic Engineer once hired. Coordination of short-term construction and long-term planning should seek to minimize damage to older utilities already under the street and assure that major street excavation in Mass Avenue occurs once, and not twice. The consultant should prepare a construction staging plan to show how traffic flow (including buses, bikes and parking) will be maintained during all major construction. The model for how not to perform road reconstruction should be Union Square in Somerville or Charles Street in Boston. Changes are needed at the Planning Board and at Community Development. Basically, the Planning Board does not plan and has not been relevant to Mass Avenue bicycle issues. Community Development lacks a useful master plan and practical competence in transportation. By 1951 the Planning Board designed and approved the original version of the Brookline Street alignment of the Inner Belt highway, and became the prime advocate for the route a dozen years before state officials adopted it as their plan. For years, the City Planning director was a prime proponent of the highway, until it was blocked in 1969. One of the consequences was the abolition of the position of City Planner and its replacement by Assistant City Manager for Community Development. Planning is too important to have the position of City Planner banished. We need to reinstate the role of the City Planner, just as we need a City Traffic Engineer. Changes to street surface operations should be coordinated with five- to ten-year construction plans by the Department of Public Works, especially for full removal of medians and any changes in sewers and other utilities planned by the Department. Special attention should be paid to coordinated actions if multiple utilities are involved. An example is Pearl Street in Cambridgeport, which several years ago went through complete reconstruction, with long delays at various points so that the street was disrupted for over a year. By general observation, actual physical work occurred less than half the time, because the schedules of utilities had not been coordinated. The curb-to-curb measurements of the existing Mass Avenue appear to vary between 65 and 72 feet. The road plan should be delineated by standard use of stationing at 100-foot spacing so that the varying curb-to-curb widths can be plotted and verified in the field. From these measurements, engineering judgments can be rendered as to the wider road sections where parking on both sides could be feasible, and the narrower sections limited to parking on one side only. Removal of “bump outs” could be considered where it makes a positive difference. Use of proper stationing will allow all street plans to be reviewed more accurately and detailed corrections made during the design process. A new master plan coordinating all four segments of Mass Ave should identify where a version of Churchill Avenue with signalized U-turns can be achieved with best effect. Provision for trailer truck delivery may be difficult because of U-turns, but existing box trucks are making U-turns by imaginative use of large commercial driveways for brief moments and backing into businesses from Mass Avenue. Consultants should analyze the best locations for signalized U-turns in a safe and consistent manner throughout the corridor, taking into account pedestrian and bike safety at the same time. Signalized U-turns can reduce conflicts between opposing movements of vehicles, while also warning vehicle drivers and bicyclists to yield to pedestrians in crosswalks, as required by state law. This concern also applies to aggressive bicycle riders, when injuries can occur to both pedestrians and cyclists in the event of a collision. Regulating bicycle movements that threaten pedestrians with bodily harm is as important as preventing “dooring” that threatens bicycle safety. A major effort to review speeding on Mass Avenue should be coordinated with design for appropriate vehicle speeds. The street today shows no evidence of posted speed limits, or speed enforcement. Traffic engineers should recommend a posted speed limit, likely to be lower than the 35 to 40 mph vehicle speeds common today in the off-peak. Observation and planning are needed to address the illegal use of the bus lanes by cars, and the mixing of high speed buses with bicycles in the bus lane. Legal and illegal loading of vehicles using the bus lane has not been addressed in past planning. Bicycle speeds are also variable, in a range between 10 and 20 mph as typical. Faster bikes are likely to use the bus lane, rather than lower speed bike lanes. Scooter use has declined, although some scooter use of the bus lane has been observed. Bicycle counts indicate only about ten bikes an hour in each direction on Mass Avenue. With time and good design, bike usage should increase. · BUS LANES and TRAFFIC : WHERE TO PUT THEM AND WHEN TO REMOVE THEM The important thing about bus-only lanes is that they are not needed everywhere. Located in the right place, they can help the flow of buses. In 2012, the original plans for Mass Avenue were designed primarily to enhance mass transit. Cambridge Traffic regulations allow bicycles to use bus lanes, and any safety implications of fast buses operating in the same space with bicycles should be carefully thought out. The height of bus mirrors should be considered, as well as passage of bikes through designated bus stops. More design work needs to be done on how bus stops and separate bike lanes will work safely and smoothly, especially if bicycle and bus volumes grow in the future. To date, there is no public evidence of traffic capacity analysis being done for Mass Avenue. Any travel time benefits for bus lane operations will depend on the ability of buses to bypass lines of congested traffic. Inbound Mass Avenue appears to have no identified levels of congested LOS F traffic and long queues. Thus the proven need for any inbound bus lanes has not been demonstrated. Where there is no congestion, separate bus lanes have a much lower priority and could be deleted. Outbound congestion occurs at Porter Square from the approach to Upland Road to Beech Street. Outbound congestion also occurs on the approach to Alewife Brook Parkway. In typical fashion, Quick-Build gave no consideration to bottlenecks along the Route 77 corridor. Determinations should be made how much travel delay time can be saved by bus lanes and how much waiting delay can be reduced when buses are operated with even spacing. DPW should present a plan to identify the utility infrastructure problem. A range of choices extends from replacing all utilities at once or selectively replacing a few. Full consideration should be given to cost, delay and disruption if doing extensive utility replacement now or spacing it out into the future. Construction sequencing plans should be assembled, with the understanding that plans may change significantly as unexpected difficulties arise. Allowance must be made to update plans when they change. A long history of trolley car and trolleybus service in Cambridge is coming to an end. The long-range plans for battery bus technology appear to be a satisfactory replacement, and trolleybus retirement can mean an end to trolley wires and poles. A past vision of Mass Avenue can be restored – as it used to be with statuesque trees lining both sides of the street. Something that today is a rather bleak 1950s-style urban arterial roadway can become more of a community avenue and continue to do so for the next fifty to a hundred years. May our trolleybuses remain peacefully in museums across the nation. Community Development may have ideas for what modern attractive streets should look like, but responsibility for designing complete streets should remain with Public Works. The advice of the City Arborist should be taken on rebuilding the “tree awning” along Mass Avenue and repairing the damage caused by the 1950s arterial highway that Mass Avenue had become. · WHAT IS THE FUTURE OF QUICK-BUILD CONSTRUCTION?? The advantages of Quick-Build policies are quickly disappearing, and the deficiencies are becoming more evident. Quick-Build appears to be a street application of the Facebook motto to “Move Fast and Break Things.” It represents one form of the arrogance of power. We should have no more Quick-Build projects and no more “House Doctor” contracts in the City of Cambridge. We should expect excellence and professionalism in all the street work the City does. For more information please contact Stephen Kaiser by email: skaiser1959@gmail.com

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |